There has been a lot of talk about the AI boom in recent years, and how it might be single handedly bolstering investor sentiment in markets worldwide.

What is less spoken about is the bottleneck that could throttle the entire industry: Advanced AI chip making, and in particular, the lack of organisations worldwide capable of producing the chips that are fuelling the current AI boom. This article discusses this issue from the lens of IP protection and strategy, and what it might reflect about increasingly competitive global markets.

Background: The Rise of TSMC and the Advanced Chip Bottleneck

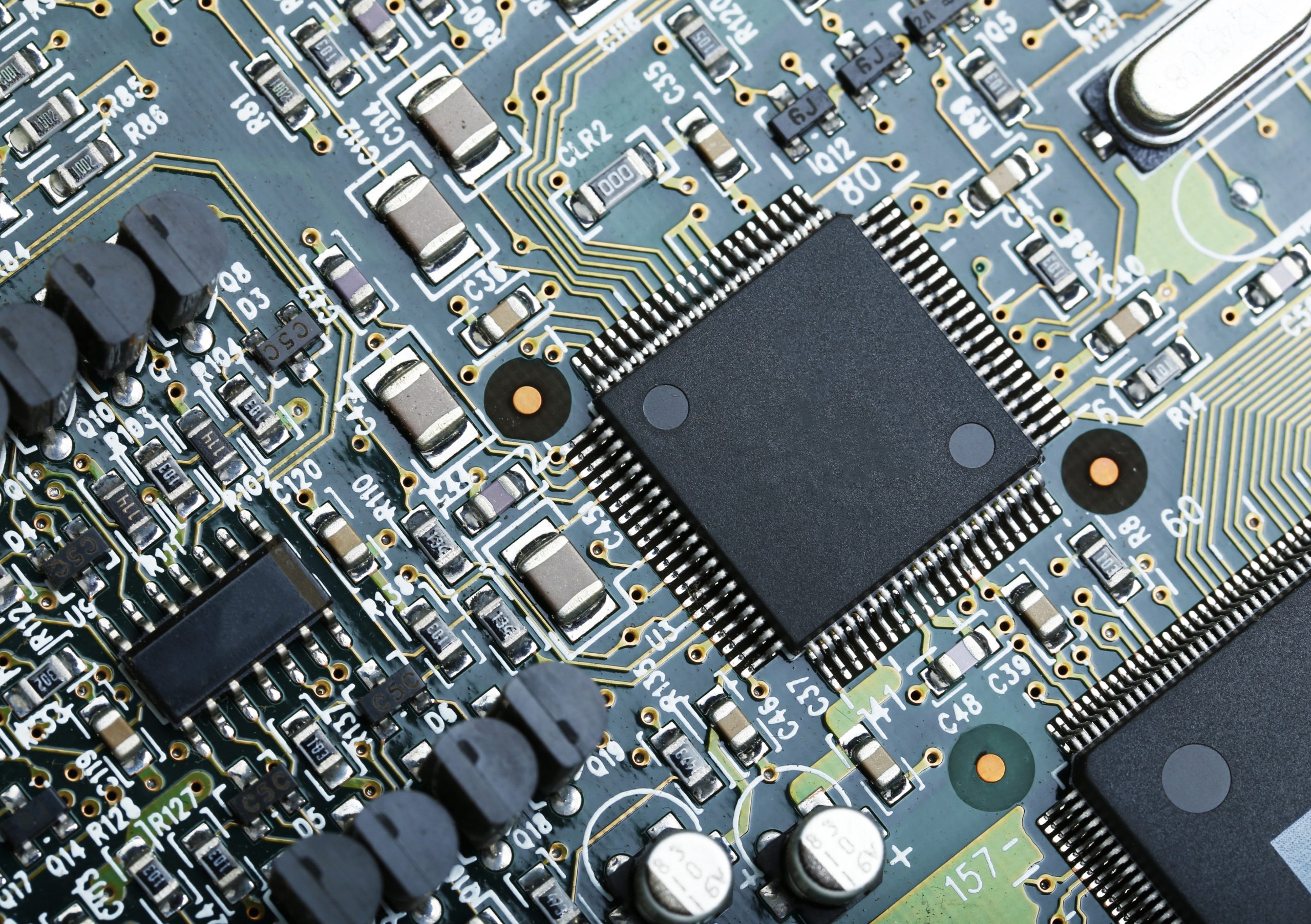

Advanced semiconductor manufacturing has become one of the most strategically important and geopolitically sensitive technologies in the world. Modern AI systems, data centre GPUs, defence electronics and consumer devices all depend on chips produced at extremely advanced and finite scale such as 5 nanometres (nm), 3 nm and soon 2 nm. However, the ability to fabricate at these cutting edge nodes is concentrated in one place: Taiwan, through the foundry giant Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company ( TSMC).

This concentration did not emerge by accident. Rather than focusing on chip design (a la, Nvidia), TSMC focused solely on manufacturing. Over time this singular focus has allowed TSMC to refine process technology faster than its rivals. As manufacturing costs soared and technical complexity exploded, TSMC became the only organisation capable of consistently delivering leading chips at scale. Even though the extreme ultraviolet lithography machines TSMC relies on to produce 3 nm chips are produced by another company in the Netherlands, ASML, simply purchasing and possessing these machines alone is not enough. The true barrier is the accumulated know-how required to integrate thousands of manufacturing variables into a stable, high yield process – a process TSMC has spent decades perfecting and protecting via patents and trade secrets.

IP Lens: Secrecy, Patents and Divergent Strategies in the Chip World

Turning now to IP strategy, patents require you to publicly disclose the invention and only provide 20 years of protection against reverse engineering or independent development. Trade secrets however stay completely confidential and can last indefinitely but offer no protection if someone can reverse-engineer or independently recreate the internal know-how. As a result, where a process or method can be kept internally confidential, trade secrets serve as valuable intangible assets that provide an incredible competitive edge.

While TSMC holds a very vast patent portfolio, it also relies heavily on trade secrets, strict access control, long term employee retention and tight supply chain management. Recent incidents in August 2025 involving attempts to extract confidential 2 nm process information resulted in Taiwanese authorities arresting and indicting three individuals, including current and former TSMC employees, highlighting how seriously the company protects its know-how.

For companies like TSMC, their tacit understanding, production culture and proprietary expertise cannot be easily reverse engineered based solely on the end products alone (i.e., a completed chip). For this reason, while competitors such as Samsung have achieved 3nm production, their yields have faced challenges, particularly in the second generation.

Fabless design companies like Nvidia, by contrast, operate in a very different part of the value chain. Their competitive strength lies in architecture, logic design, interconnect schemes and the hardware software co-design that powers AI acceleration. These elements suit patent protection more so than manufacturing know-how, because they are more formally definable and more vulnerable to reverse engineering. Nvidia therefore maintains a vast and fast growing global patent portfolio that covers GPU architecture, AI compute pipelines, memory hierarchy and specialised processing features.

In simple terms: Nvidia patents the design. TSMC protects the process. Each strategy is shaped by the type of technology the company creates and the threats each faces.

A similar dynamic is visible with other players trying to challenge TSMC at the leading edge. Samsung has committed heavily to competing at the 2 nm node. Its portfolio features a mix of device level patents, memory architecture patents and process specific filings. This reflects a hybrid model that mixes patent protection with internal process secrecy. Even so, Samsung still faces the execution gap that has kept most competitors behind TSMC. Intel’s revitalised foundry ambitions follow a similar pattern, with extensive patent holdings but ongoing difficulty in achieving consistent high yield performance at advanced nodes. These examples demonstrate that strong patent portfolios signal investment but cannot substitute for decades of accumulated manufacturing expertise.

Moving Forward: Geopolitics, AI Growth and the Future of Semiconductor IP

The strategic importance of advanced chips is now attracting the attention of governments worldwide. The AI boom has made high end silicon a national priority, prompting massive investment from the United States, China, Japan and Europe in attempts to localise or diversify semiconductor supply chains. Yet despite these efforts, the cutting edge remains centred in Taiwan.

This raises difficult questions: Can any new entrant realistically catch up to TSMC’s tacit process knowledge? Will the drive for technological sovereignty intensify patent disputes or accelerate the use of licensing, export controls or trade restrictions? And how will the balance between design-centric companies like Nvidia and manufacturing-centric giants like TSMC evolve as AI workloads demand ever more advanced chip technology?

What becomes clear is that the semiconductor industry illustrates a fundamental principle of intellectual property strategy: The optimal protection method depends entirely on the nature of the asset. Designs that are visible and reverse engineerable typically require patent protection. Processes that are tacit, experiential and operationally complex are often best protected through secrecy and organisational culture.

As the world enters the next stage of AI and high-performance computing, these divergent IP strategies will shape not only the competitive landscape of the semiconductor industry but also the geopolitical balance that depends on it.